Photo: UNDP

Mon State in the south east of Myanmar lies sandwiched between the Andaman Sea to the west and the Dawna Mountain range to the east. On sunny days it presents stunning vistas, but during the rainy season it is often beset by devastating weather. The narrow coastal land on which it is situated has always been hammered by heavy storms during the monsoon season, often causing massive flooding that damages homes, infrastructure, farms, and plantations.

“Monsoon is the time we are anxious about; it brings rains to our cultivations but too much of it often brings destruction,” said 26-year-old Ma Nway Nway Thet, a native of Kyaung. Her village, 12 miles east of the town of Ye, is one of the most vulnerable to storms and flooding.

Myanmar is one of the most disaster-prone countries in the world. It ranks second out of 187 countries in the Global Climate Risk Index of countries affected by extreme weather events, over the past two decades. It is vulnerable to a wide range of hazards, including floods, cyclones, earthquakes, landslides, and tsunamis. Mon State is one of the hardest when natural disasters strike. Over the years, it has been hit by a series of floods but 2018 and 2019 were particularly bad, when the state experienced heavy flooding that destroyed homes and plantations.

Nway Nway Thet remembers well the floods of 2019.

“One day in August, the government announced there would be unusually heavy rains, and we were duly alerted. It rained on and off for a week, and then the floods came,” said Nway Nway Thet. When the streams overflowed, the whole village fled to the monastery compound on high grounds. A number of houses were washed away. In addition, paddy fields and rubber plantations, the mainstay crops of the region, were all destroyed. “It was the worst flood so far,” she added.

After that flood, people from her village decided that they would no longer be passive in the face of disasters. So, Nway Nway Thet said they formed a committee that would help with response and recovery efforts, following natural disasters. Getting organized was relatively easy. But, the committee, which includes Red Cross volunteers lacked expertise and knowledge about operating procedures, said Nway Nway Thet.

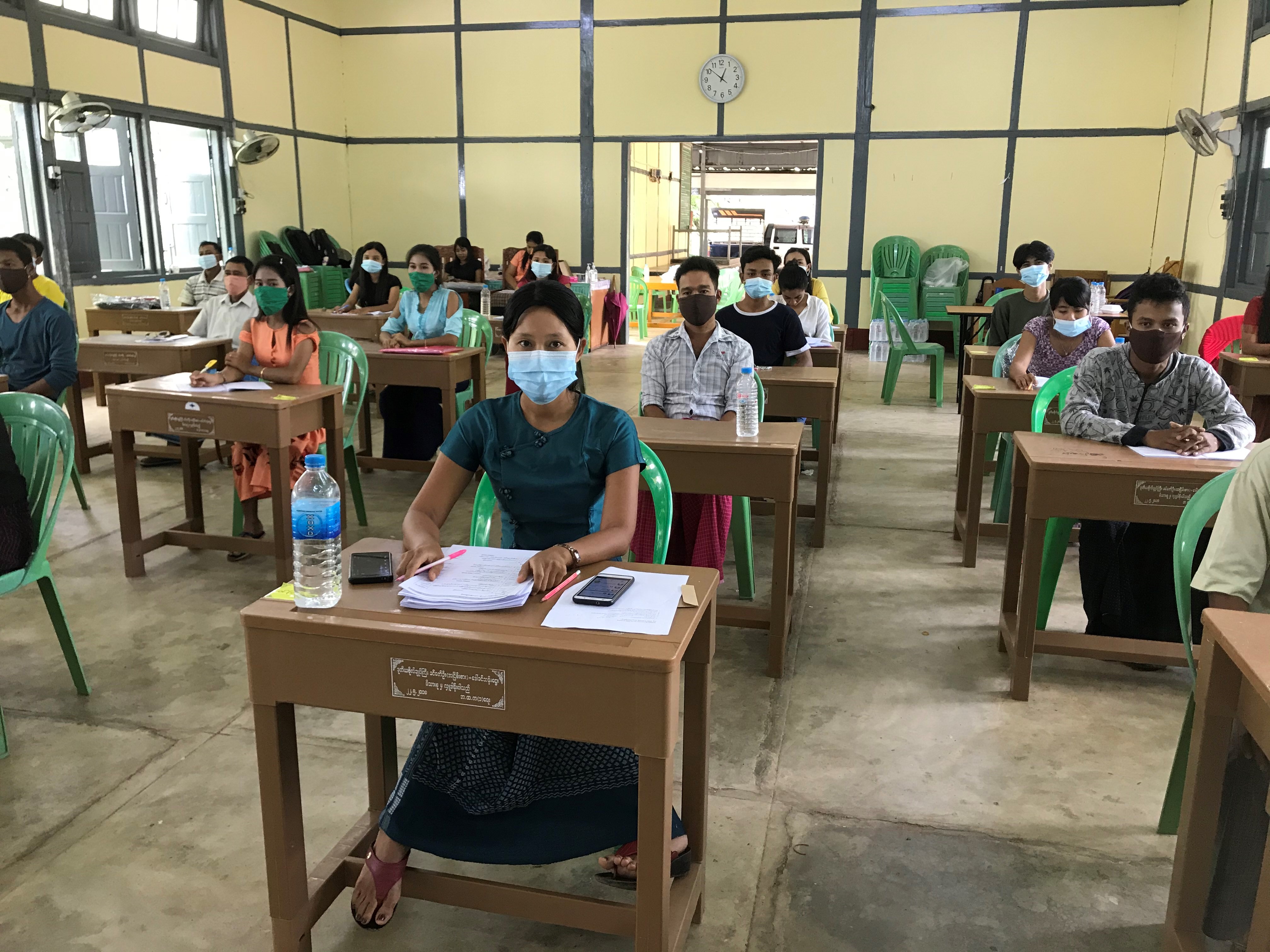

In August this year, her committee and other disaster risk reduction committees from neighboring communities, in Ye Township, were invited to attend disaster risk management training, that was supported by the UN Development Programme (UNDP), with funding from the Government of Luxembourg.

Mon State’s Disaster Risk Reduction Working Group (DRRWG) working with UNDP developed the three-day training programme that included response and recovery procedures. The training sessions were held in four of the most flood prone townships: Bilin, Paung, Kyaikmaraw and Ye – that include 122 villages and 39 wards.

“We learned all things necessary to implement before, during, and after a disaster. We learned how to select a camp site, to prepare it according to health requirements, and to effectively and safely manage the camp,” said Nway Nway Thet. “We have been doing these things for years on our own, but only now we have learned the standard operating procedures (SOPs) for all these issues. SOPs will save us a lot of troubles in future.”

The DRRWG sessions included search and rescue training, the use of global positioning systems (GPS), relief and rehabilitation, emergency communication and coordination, first aid, and recovery assessment and planning. Emergency response kits were also provided to the trainees.

Gender awareness was an integral part of the training, said Ni Ni Lwin, head of UNDP’s Mawlamyine office. “We worked with our colleagues from the UN Population Fund (UNFPA) to share knowledge on gender equality and other related issues. Our goal during the training sessions was to raise gender awareness among rural communities.”

It has for Nway Nway Thet and her team. She said previous campsite shelters did not consider gender issues such as bathing space and toilets. Now her team incorporates these concerns into plans, and she believes such measures will help prevent gender-based violence.

“Before we always felt anxious when we heard news about adverse weather, but less so now,” said Nway Nway Thet. “We have learned much more and are now better prepared to reduce the impacts of flooding,” she added.

Locations

Locations