Crossing boundaries: Scaling work experience through multi-disciplinary experiential learning

July 30, 2024

By Victor Apollo

Work is a fundamental part of most people’s lives, providing numerous individual, social, and economic benefits. However, the preparation that learners receive in higher education often falls short of meeting the demands of the modern job market. In Kenya, this gap is acutely felt, with youth unemployment at a staggering 67%. This issue is further exacerbated by the lack of practical work experience demanded by employers.

How easy is it to obtain opportunities for quality work experience?

As part of their diploma or bachelor’s degree requirements, students in Kenya must pursue attachments — an important component of education and training, which provides students with real practical work experience in their areas of specialization as a course requirement in most post-secondary training institutions. This integration of work experience into the diploma or degree program is crucial in equipping students with the skills, connections, and confidence to navigate their career paths and shape their futures. Despite the graduation requirement and the substantial body of evidence highlighting the value of attachments, many students in Kenya face challenges in securing relevant placements.

Furthermore, even among those who manage to secure placements, there is a concern that they may not be gaining practical experience that aligns with the demands of the job market. Limited communication among stakeholders appears to be a significant factor contributing to this issue. The timing for attachments is typically uniform across most institutions, leading to a surge in demand for opportunities simultaneously. Moreover, companies often refrain from advertising attachment openings. Consequently, securing a placement is challenging for students, particularly outside major cities like Nairobi, where personal connections become disproportionately influential. Faculty members mentoring students feel the strain of financial and time constraints, which often curtails their ability to travel to work sites for supervision and engagement with students on attachment. Additionally, they rarely allocate space for students to share their attachment experiences with one another post-attachment.

Consequently, knowledge gained by one cohort of students is not effectively transmitted to subsequent cohorts, hindering their ability to envision and optimize their attachment opportunities.

According to a research study announced by Consumer News and Business Channel (CNBC), 70% of all jobs are not published publicly and 80% of jobs are filled through personal and professional contacts. These jobs are either posted internally or are created specifically for candidates that recruiters meet through networking thus signaling the importance of networks in unlocking work and support. On the contrary, the current education system is not designed to build social capital.

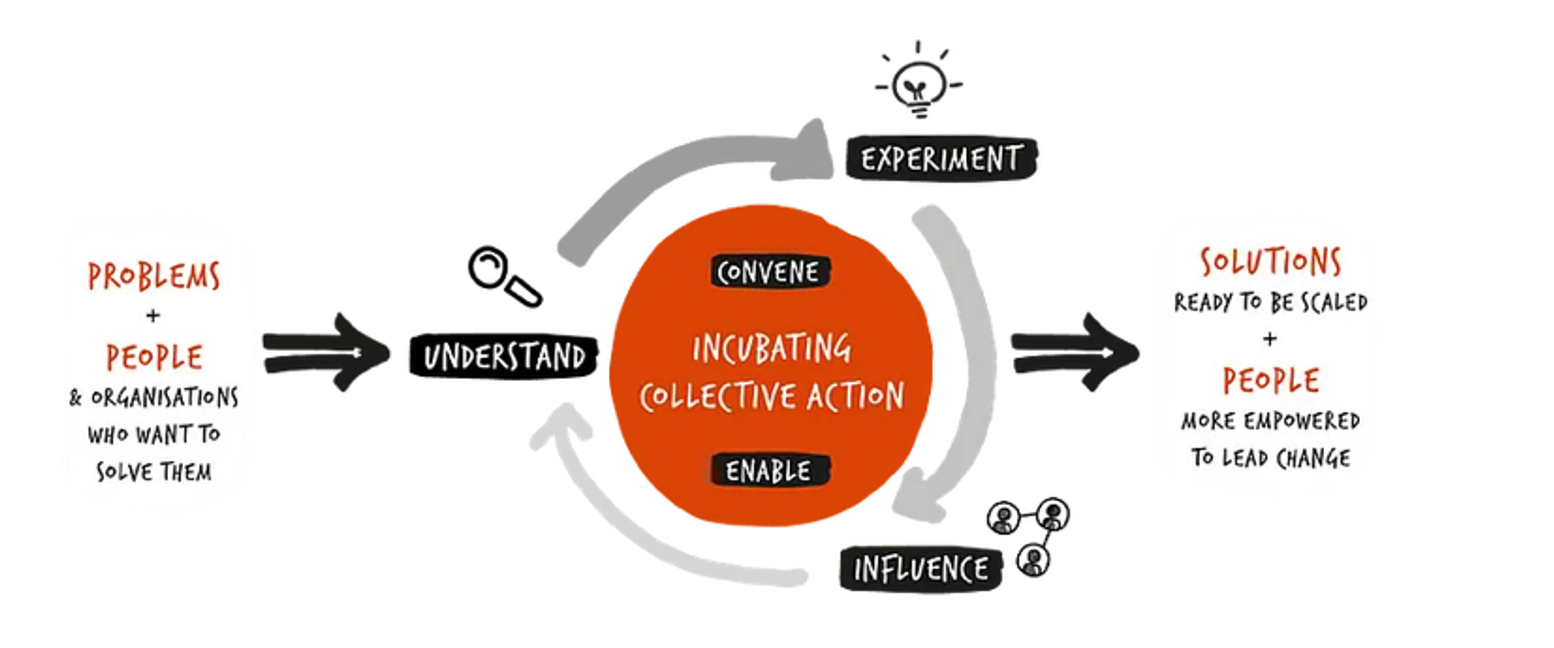

At the youth side event held during the 6th Kenya Institute for Public Policy Research and Analysis (KIPPRA) Annual Regional Conference in June 2023, young people clearly expressed their frustrations and challenges. The UNDP Accelerator Lab in Kenya had partnered with KIPPRA to host the side event as part of their exploration of a learning cycle that aimed at broadening work experience avenues for post-secondary students through alternative channels. The side event provided a platform to share initial learnings and outcomes emerging from the Lab’s learning cycle.

Weak signals of change

An emerging trend among youth involves leveraging social capital via social media platforms to access job opportunities and support networks. By sharing experiences, recommendations, and job leads within online networks, young people create a supportive community that enhances their employment prospects. This strategy involves the strategic use of hashtags to reach wider audiences and attract potential employers.

This dual strategy of mobilizing social capital and algorithmic manipulation reflects a sophisticated understanding of digital ecosystems, underscoring a new paradigm in accessing work and support in the digital age.

The strength of weak ties: Broadening, deepening and diversifying student networks by scaling access to industry professionals

The 21st-century learning model emphasizes not only dispensing knowledge but also developing lifelong learners who are critical thinkers and problem solvers. Given the complexity of today’s world, problems cannot be solved using only the intellectual tools of a single academic discipline. Yet, few college graduates have experience analyzing problems from multiple disciplinary perspectives.

Social connections play a crucial role in helping people find jobs. Practitioners like Hilary Cottam have highlighted the importance of relationships in finding work and demonstrated practical ways to strengthen social connections. With increasing higher education admissions, equipping next-gen talent to meet society’s needs has become more urgent. A socially connected, adaptable, engaged workforce is essential to navigate current transitions and future challenges.

Our learning question:

At the UNDP Accelerator Lab in Kenya, we observed firsthand the challenge of limited work experience opportunities, where one internship vacancy could attract hundreds of applicants. Concerned about those missing out, we explored ways to scale work experience opportunities and reduce the network gap among students.

Our primary learning question was: How can we deliver work experience at scale while reducing the network gap among students in higher education institutions? Initially, we conducted web scraping of online internship advertisements to understand employer expectations. Using this insight, the Acc. Lab mapped alternative spaces where students and recent graduates could develop sought-after skills. One such space, offering short-term opportunities, included conferences, workshops, and meetings. Notably, report writing emerged as a critical skill sought by employers mainly in the development sector. Many organizations hold conferences or workshops, which can provide opportunities for several students to serve as rapporteurs. By participating in such events, students not only enhance their report writing skills but also gain industry insights and expand their professional networks. Structured five-day workshops can prove more impactful than unstructured three-month attachments. Encouraging young people to engage in these spaces, facilitated by the supply side, broadens access to networks they might otherwise lack.

The experiment design — Multidisciplinary experiential learning

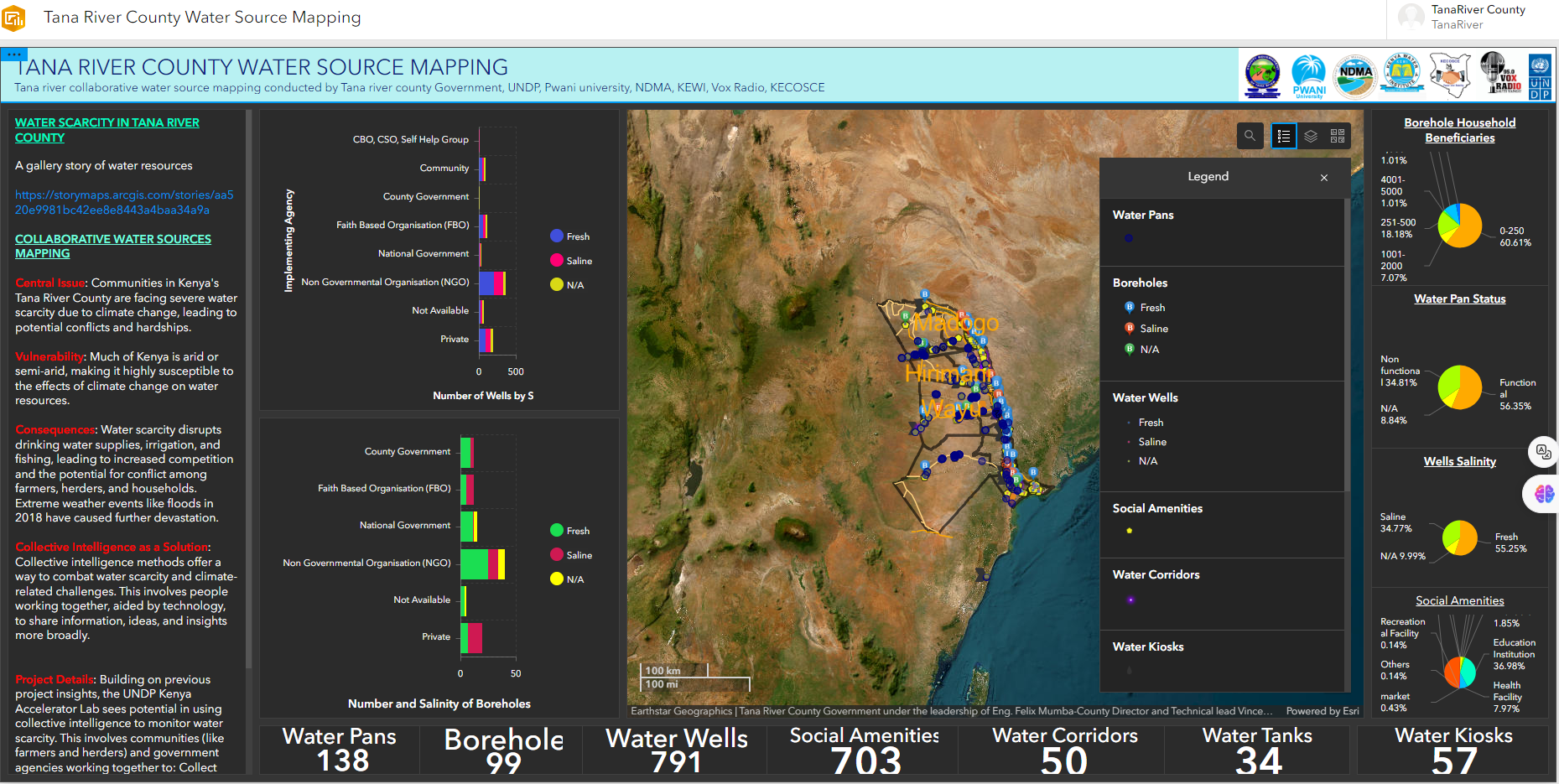

The Accelerator Lab also initiated micro-projects, short-term interdisciplinary projects lasting up to three months. One such project involved 21 students and nine lecturers from Pwani University and Kenya Water Institute. Together, they addressed water insecurity challenges arising from climate change. Using a Living Lab methodology and design thinking framework, stakeholders moved from identifying problems to designing and testing prototypes.

The initial engagement involved a kickoff workshop to co-design a digital collaborative map for water infrastructure projects. Subsequent phases included community engagement and data collection, culminating in developing a prototype and training 43 community data stewards to clean, analyze and visualize the collected data, test the digital prototype with community and stakeholders and incorporate the feedback in the final map.

Learning journeys curated during the challenge-driven process enabled students to understand the interconnected nature of issues and their broader societal implications, fostering deeper thought and engagement with the world while building lifelong community connections. Collectively, the interdisciplinary team developed a collaborative platform for mapping water resources in Tana River County.

By assembling multi-disciplinary student teams to address complex problems, we harnessed diverse knowledge for innovative solutions. These teams worked on a micro-project alongside external organizations, revealing that accelerated and deeper learning occurred when students engaged directly with real-world challenges. The integration of theory and practice was enhanced, and peer dynamics fostered greater dedication among team members. Our findings highlight the superiority of collaborative, real-world projects over traditional internships, providing clearer objectives and more impactful outcomes.

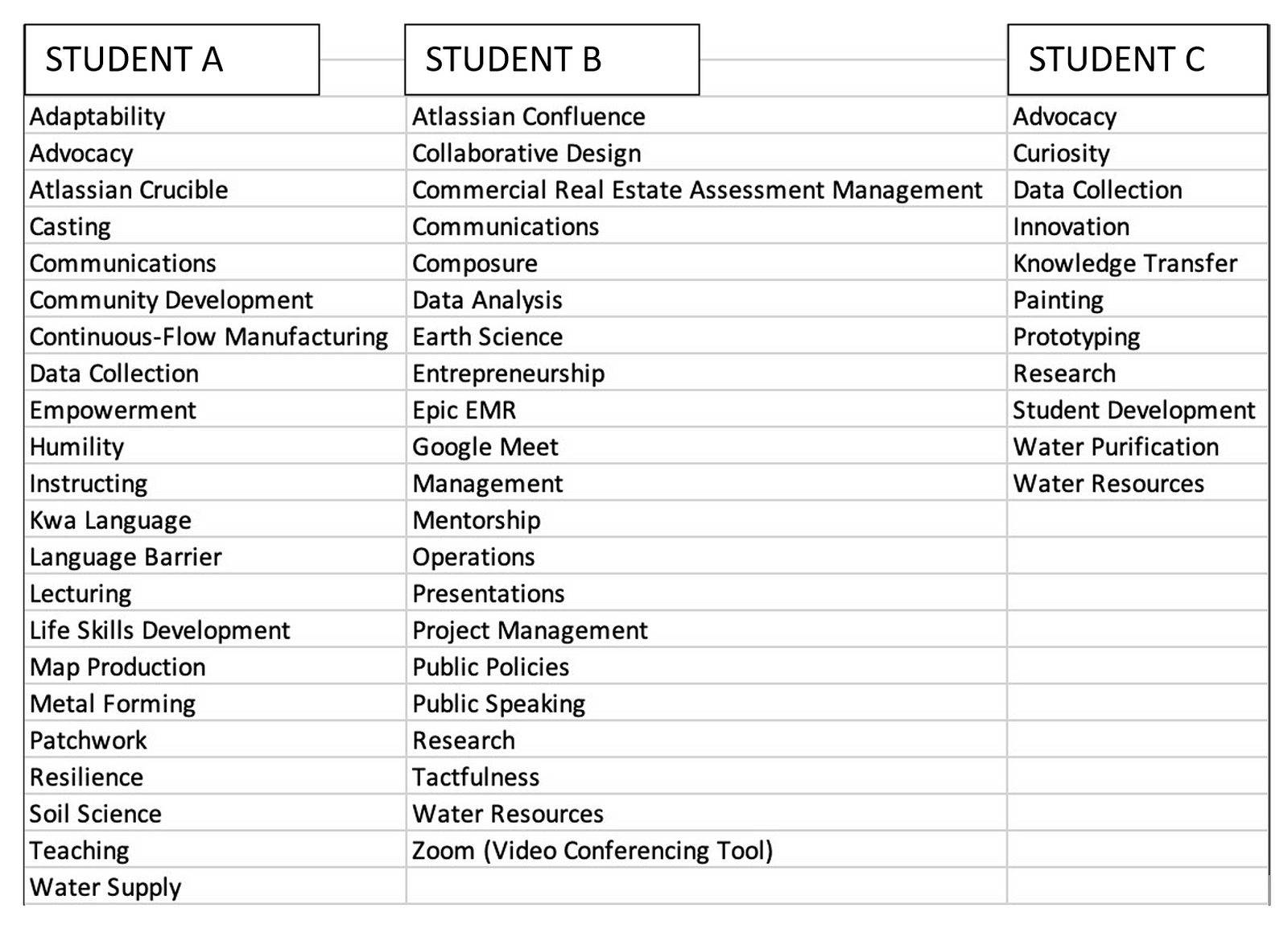

Students were tasked with writing blogs detailing their experiences. These blogs underwent analysis by an Artificial Intelligence (AI) engine, which distilled the diverse skill sets acquired by students through their engagement in the interdisciplinary project. The ensuing skills gained by three students from a cohort of 21 students after working on the micro-project are listed below:

Key takeaways

Many of the complex challenges we face require large-scale collaboration. Design thinking and systems thinking provide us with a means to leverage interdisciplinary teams across various institutions to tackle these complex issues effectively.

Our interdisciplinary approach empowered 21 students to explore roles in previously unfamiliar sectors, such as the intersection of history and water scarcity and the application of computer science in water management. This exposure to diverse perspectives and skills enriched their education and better prepared them for post-graduation life, making them more attractive to employers.

Employers benefit from investing in interdisciplinary experiential learning internships by gaining innovative ideas and fresh energy. These interns, supported by strong ecosystems, contribute valuable technology skills and digital expertise, enhancing organizational competitiveness.

What’s next?

To scale this approach, we propose:

Academia: Convert classroom experiences into collaborative problem-solving events led by facilitators to enhance the relevance and context of learning.

Government, non-profit and private sector involvement: Open challenges for students to work on, facilitating interdisciplinary collaboration to address national issues through innovative solutions.

Informal sector integration: Engage students in the informal sector for hands-on experience, fostering an entrepreneurial mindset and innovation.

Development of a playbook: Create a guide for stakeholders to outline alternative learning spaces and potential skills students can acquire.

Call to action: Closing the network gap — where some students benefit from who they know — demands a collective effort. Encourage industry professionals to share their time, talent, and connections with students lacking resources. Retired professionals can also contribute their expertise to help forge a brighter future for young people.

For those interested in replicating this approach, seeking further information about this work, or exploring collaboration on future initiatives, please reach out to victor.awuor@undp.org via email.

About the author

Victor Apollo is the Head of Solutions Mapping at the UNDP Accelerator Lab in Kenya. In this role, he leads lab efforts in deep community immersion to explore, document, and increase understanding of emerging methods of tapping into bottom-up solutions related to sustainable development. Furthermore, he is tasked with designing specific field research and participatory methods to focus on the most vulnerable populations and those not usually engaged in public policy debates on development methods.

Locations

Locations