A young boy rests under a long-lasting insecticidal net in the Solway area of Sanma province, Vanuatu.

How long-lasting insecticidal nets are bringing Vanuatu ever closer to being malaria-free

“To protect myself and my family, we keep our yard clean, we make sure there are no tins, or bottles or coconut shells lying around, and cut the grass regularly. And we sleep under a mosquito net,” says Carol Samson, a local resident in the Narara community of Sanma province, in Vanuatu.

The province of Sanma is located in northern Vanuatu. Home to approximately 59,000 people and the largest island, Santo, it is one of the remaining malaria strongholds in this tropical archipelago.

Malaria-carrying mosquitoes breed in stagnant, standing fresh water. On their property in Sanma, Carol Samson and her family follow the recommendations of malaria control officers to eliminate potential sites for mosquito breeding and use long-lasting insecticidal nets.

Globally, there were an estimated 228 million cases of malaria in 2018, claiming the lives of over 400,000 people. Children under the age of five are most vulnerable, accounting for 67 percent of all malaria deaths.

In Vanuatu, malaria has historically been one of the leading causes of ill health. However, sustained and coordinated efforts by the Ministry of Health’s National Malaria Programme, in cooperation with the World Health Organization (WHO), the United Nations Development Progamme (UNDP), the Global Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria, the Australian Government, Rotarians Against Malaria and other partners, have brought significant reductions in malaria prevalence.

Confirmed cases, deaths and annual parasite incidence (API — new infections per year, per 1,000 population) have declined significantly since 2000. The number of cases has dropped from a high of over 15,000 in 2003 to 576 in 2019.

The provinces of Sanma and Malampa continue to have API above 2.5, and are therefore the sites of intensified malaria elimination efforts.

This has been achieved while overcoming serious disruptions, including volcanic eruptions prompting the full evacuation of Ambae island in Penama province in 2017 and 2018. The country also faces frequent tropical storms and cyclones such as the recent category five Cyclone Harold which has prompted emergency net distributions to areas most severely affected.

In 2017, the southern province of Tafea was declared malaria-free. Drawing on lessons from Tafea, complete elimination nationwide – once a pipe dream – is now within reach.

The Ministry of Health is now projecting zero local malaria cases across the whole country by the end of 2023.

To achieve this, UNDP is leading a project that is scaling up distribution of long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs), with support from the Global Fund, specifically targeting the medium- and high-risk parts of the country. Over the 2018-2020 period, more than 200,000 LLINs are being given to households.

Guy Emile started working with the National Malaria Programme in 2010. Since 2015, he has been responsible for the overall management of LLIN distribution in the country.

It’s a complex operation, says Guy Emile, LLIN Senior Vector Control Officer at the Ministry of Health. “Every year we distribute. After three years, we replace the bed nets,” he explains.

“This is a major operation and it involves most of the Public Health officers in the provinces.”

Under the National Malaria Programme, and with support from the Global Fund, UNDP procures the LLINs for the Ministry of Health.

A national storage centre houses the stockpile until distributions are carried out in the provinces.

Bringing down the incidence of malaria requires close to universal access to and consistent use of LLINs. For this to happen, numerous challenges must be overcome.

“I think the main challenges is access to basic information, such as information about the population and households, which is not always available from the provinces” acknowledges Guy.

“This is crucial because based on that information, I calculate the number of nets a community needs. It has happened a few times in the past where the information provided was not accurate. I encourage them to collect information, even if it is not accurate, but near enough to accuracy. That is important.”

To achieve maximum impact, health workers conduct awareness raising activities in the local communities in advance of the distributions.

“Before teams visit the communities, there are messages we pass on to the community leaders, who then inform people through church services, or meetings called by the chief or the local leader, telling everyone what we are coming to do,” adds Guy.

Health workers also educate people in the communities on how to properly use the nets.

“Before we actually start distributing, we must carry out some awareness first with the locals. This is to tell them how they are supposed to use their nets, how they are supposed to maintain them,” says Guy. “We also get them to actually use the nets, because their contribution is also very important. We tell them we could not achieve elimination all on our own, that we need their contribution as well.”

According to Brisit Malisa, a Neglected Tropical Diseases Officer at Sanma Provincial Health Office, people welcome the health promotion efforts with open arms.

During this year’s LLIN distribution campaign, Brisit Malisa was involved in distribution in Zones 1 and 7.

“Normally, in a given day, the total number of nets we can give out is 300 or 400 plus. We tell them that if you use the mosquito net to sleep under, mosquitoes are scared to come because when they do, they smell the chemical that is in the net, consequently the mosquitoes simply fly around. You can sleep under a net at night, you can chit-chat inside it, you can do anything, because you know you are protected against mosquitoes,” says Brisit.

“When we do effective awareness, when we advise the communities that on such and such a day we will be there, and there should be one person in the household present to receive the nets, then you see that people are happy,” she says.

“Distribution is made to every single person in the household because once one of the household dwellers gets malaria that means that they are a carrier and transmission can happen, with everyone at risk of being infected.”

Awareness raising activities are held with small groups of people, sharing good practices of using LLINs.

Casimir Liwuslili, Health Promotion Officer at Sanma Provincial Health, emphasizes the need for sustained efforts. “The number of cases is dropping significantly. However, there are still a lot of cases occurring in Sanma, and also in Malampa.”

“We say, wherever you go, if you go somewhere like to the bush, please take your net with you. The net is your property, you must look after it to ensure the net lasts until the next distribution. And that their first concern is not for themselves, but for the children, to make sure they sleep under a bed net,” he says.

A native of Pentecost, Casimir Liwuslili has nearly 25 years of experience working in health promotion in Sanma.

The experience of Esther, a young mother who lives in Malekula, drives home the realities of the malaria control efforts.

“It helps a lot,” says Esther, referring to the LLIN distribution campaigns. Esther’s son, now two years old, contracted malaria the first week after he was born.

Asked what their family does to ensure their son does not get malaria again, she responds: “We sleep under a mosquito net, I never let him sleep outside. I will keep it this way until we go and get new nets."

Esther, after receiving a new set of LLINs near her home in Malekula.

The provision of high coverage of LLINs makes up a core part of the intensified malaria control programme initiated by the Ministry of Health and its partners in 2004. UNDP has the lead role in supporting procurement and distribution of LLINs with the Ministry of Health, and also, in partnership with WHO, supports strengthening of surveillance systems and diagnostic capacity, and seeks to help establish long-term financial sustainability for the National Vector Borne Disease Program.

Stagnant water, a prime breeding ground for mosquitoes, lies in close proximity to homes in Sanma's Sarakata area.

As Esau Naket, Malaria Case Management Officer at the Ministry of Health, explains, malaria is also closely associated with poverty and the country’s overall development.

“When a person is sick, they cannot work, they cannot earn enough money. If not treated properly, it can cause death. That is the impact, on communities and on our society,” says Esau Naket. “Malaria is a sickness related to poverty. If you have a good house, if you have a standard of living where you eat well and the environment you live in is good, then you are unlikely to get malaria.”

“Now that we have elimination in the southern part of the country, we see the tourism industry in the Tafea region increasing, because now people can move freely there, because it is malaria-free.”

Esau Naket at his office at the Ministry of Health in Port Vila.

The last step of full elimination can be the most difficult.

“We can reduce malaria, but getting the last parasite will be hard. We need the resources, and we need commitment, both politically and from the malaria programme officers in order to end malaria. If we have the resources, but no commitment, we can’t achieve it. It’s the commitment that drives it.”

While the world is seeing a range of technological advances, including a promising vaccine and new treatments, the tried and true bed net remains a critically important tool.

“My advice is that if anybody has a fever, please, go to the nearest facility to be tested for malaria. And I advise everyone to sleep under a mosquito net.”

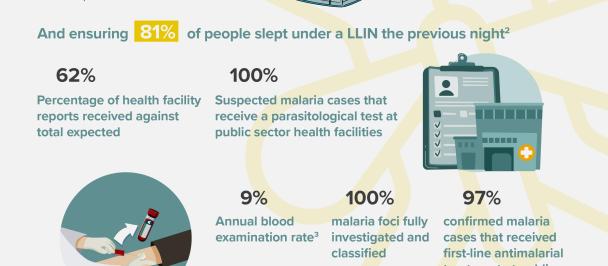

Ensure 81% Coverage of Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs) in Vanuatu is a three-year (2018-2020) programme supported by the Global Fund and implemented by UNDP in collaboration with the Ministry of Health. The programme seeks to maintain 81 percent coverage of LLINs in the population, ensuring that each household has at least one LLIN, and that all children under 5 years old and all pregnant women sleep under LLINs. For more information, visit our website.

Authored by Ian Mungall, UNDP, and Sheryl Mahina, UNOPS. Photos by Sheryl Mahina, UNOPS.

Locations

Locations