Towards Comprehensive Care Systems in Latin America and the Caribbean

Who cares for the women?

December 13, 2022

The fact that women bear a disproportionate burden of unpaid care work is widely known and well documented. In one of the first #GraphForThought posts back in 2019, we discussed how female labour force participation remained low partly because of the time constraints associated with care responsibilities.

The pandemic only deepened this problem. It evidenced that care, both paid and unpaid, is essential to sustain the economy and society. The various lockdowns, curfews, school closures and quarantine policies considerably increased the burden of care in homes, especially for women. The pandemic also highlighted the importance of community care, as it was key to the survival of large sectors of the population in conditions of vulnerability and lack of protection.

According to data from ECLAC, in 2020, women suffered an 18-year setback in economic participation rates, going from 51.8% in 2019 to 47.6%, while drastically increasing their domestic tasks, which already occupied between 22 and 42 weekly hours before the pandemic. As economies recovered, according to ILO data, women have not reentered the labor market at the same rate than men: more than 4 million jobs held by women disappeared in the context of the pandemic. The gender penalties of the pandemic also extended to different types of households. As a previous #GraphForThought showed, single-mothers are seeing faster labor market recovery rates than mothers in multi-parent households.

Using data from the World Bank and UNDP’s High-Frequency Phone Survey (HFPS), Phase 2, Wave 2[1], this #GraphForThought looks at the changes in care burden for both men and women, and how this relates to changes in employment.

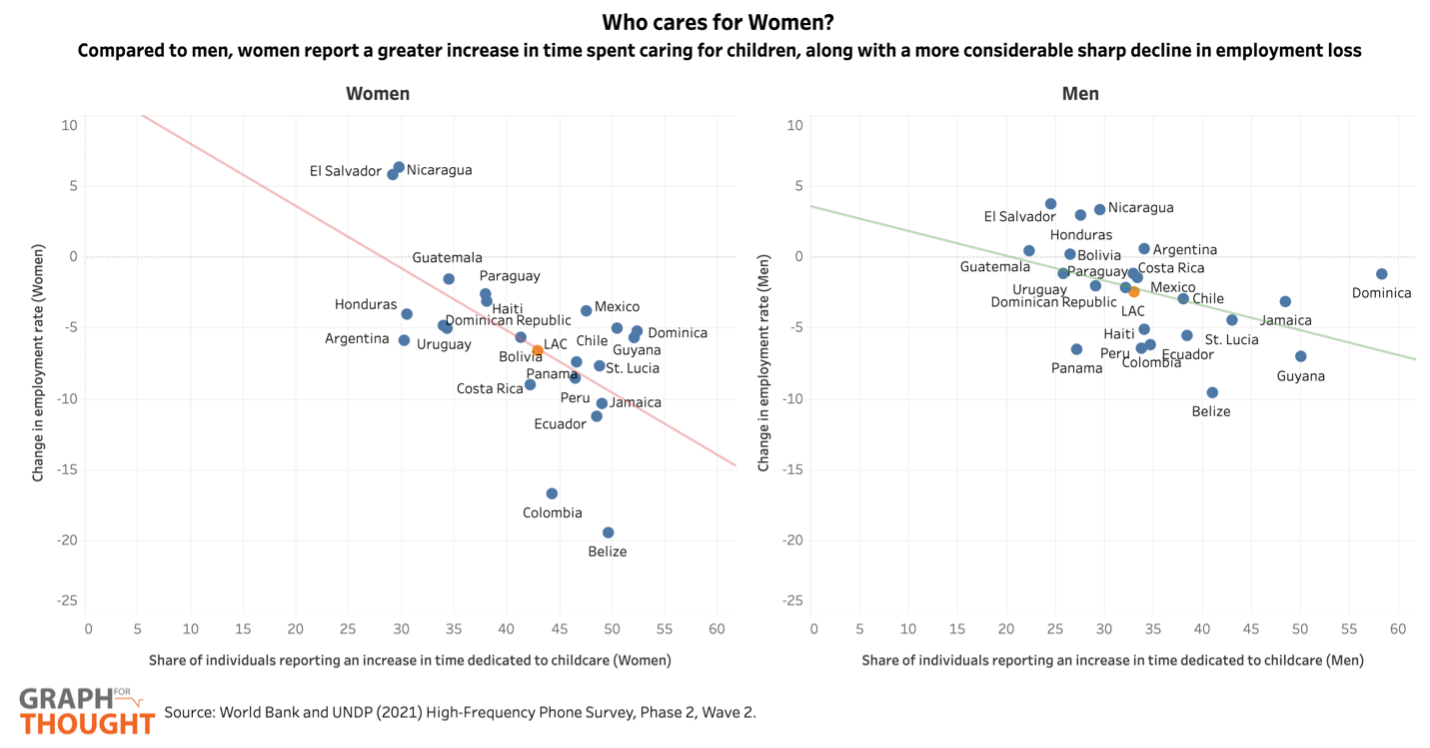

As the figures below show, both men and women experienced an increase in time dedicated to childcare (for children up to 17 years old) and changes in employment rates (from Feb 2020 to the end of 2021). However, the impact on women is significantly more pronounced.

On average, 43% of women reported an increase in time dedicated to childcare in 2021, 10 percentage points higher than the portion of men that reported increase childcare (33%). In some countries, the share of women reporting an increase in time dedicated to childcare exceeded 50%, with the highest shares in Dominica and Guyana.

At the same time, while employment rates decreased for both women and men, they declined more sharply for women (7 and 2 percentage points, respectively). Declines in female employment rates range from 19 percentage points in Belize to 6 percentage points in El Salvador and Nicaragua.

Given this disproportionate impact, the question is: how do we ensure that women are not left out of the economic recovery due to their burden of care? This is one of the main topics discussed at the XV Regional Conference on Women in Latin America and the Caribbean in Buenos Aires, which brought together representatives of 30 countries to shared innovative experiences in expanding care services. In the Buenos Aires Commitment, countries pledged to continue to “adopt regulatory frameworks that guarantee the right to care through the implementation of comprehensive care policies and systems from the perspectives of gender, intersectionality, interculturality and human rights”.

There is momentum around strengthening care services. Since 2020, several countries have implemented relevant policies. For example, Argentina created the Federal Care System; in Colombia, Bogotá created a district Care System; Costa Rica approved a National Care Policy 2021-2031; at the end of 2020, the Mexican Chamber of Deputies approved a reform that elevates the right to care to constitutional status, while creating a Care System. More recently, Chile launched a platform to identify caregivers in their Social Registry, allowing them to get a credential and priority access to government benefits.

The care economy is a sector that can provide dynamism in the post-pandemic recovery, with multiplying effects on well-being, productivity, growth, and fiscal systems. A new fiscal pact to finance universal, inclusive, sustainable and gender transformative social protection systems is needed, including care systems as a key pillar.

[1] The second wave of the HFPS, which was collected between October 2021 and January 2022, includes a total of 22 countries: Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Guyana, Haiti, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, St. Lucia, and Uruguay.

Locations

Locations