Starting in the 1950s, Latin America and the Caribbean underwent a rapid urbanization process, making it one of the most urbanized regions in the world. Today, 82% of the population lives in urban areas, compared to the global average of 58% (Figure 1). While cities can offer abundant opportunities for improved well-being, they also present challenges, especially during times of crises, that can make households more vulnerable to poverty.

This #GraphForThought examines urbanization and poverty trends in Latin America and the Caribbean (LAC) using data from ECLAC and UNDESA. Over the last two decades, LAC has made very significant progress both in terms of extreme poverty and poverty reduction. Despite setbacks since 2014, 2022 saw the region’s lowest poverty rate ever (26%), with slight declines projected for 2023 (25.2%) and 2024 (25%).

But the face of poverty is changing in LAC. Although rural poverty rates remain higher, the number of urban poor continues to rise faster. Figure 2 shows that the share of the poor living in urban areas increased from 66% in 2000 to 73% in 2022. The shift is even more dramatic for extreme poverty, with the urban share rising from 48% to 68% over the same period.

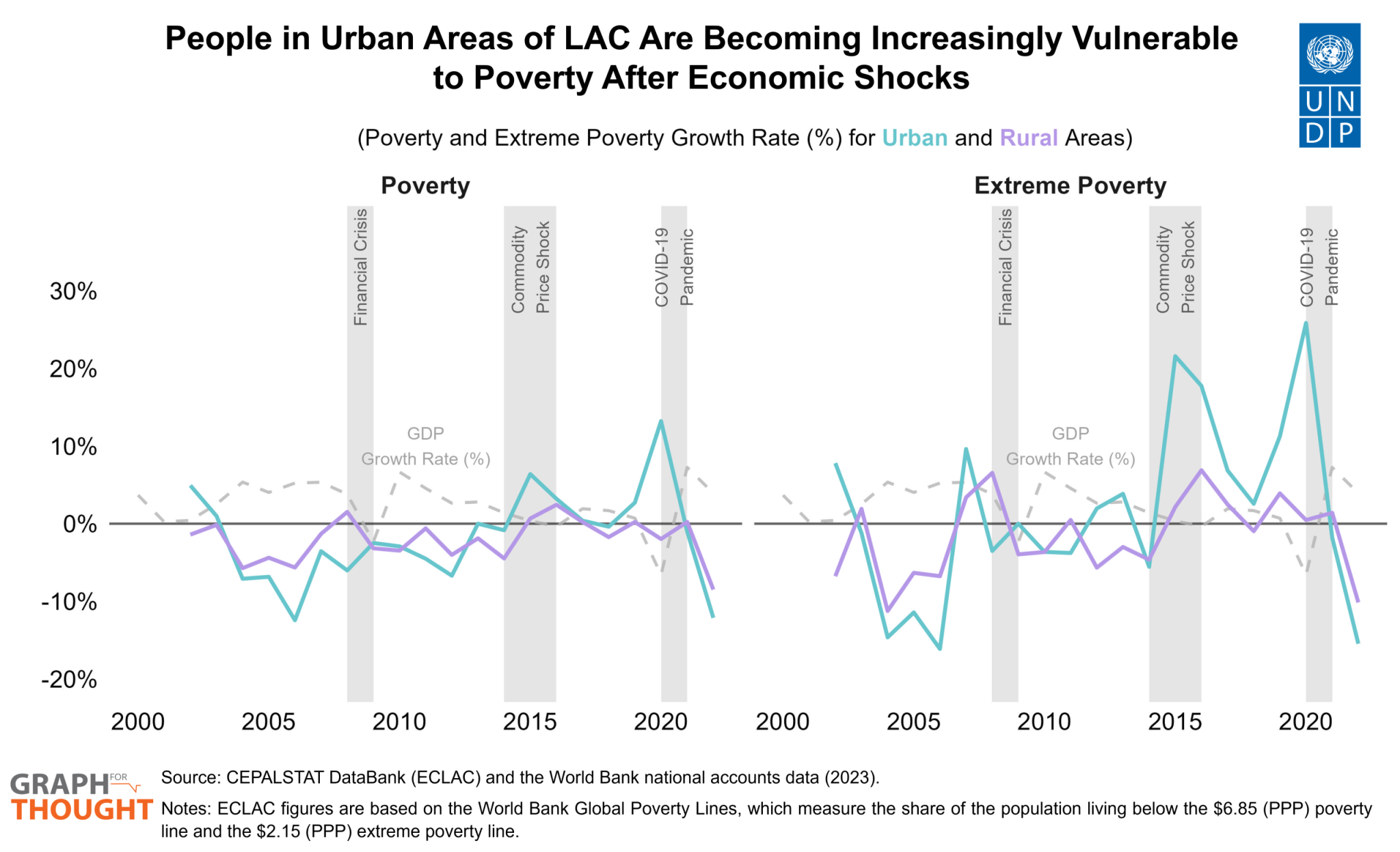

While many move to cities to find improved employment prospects and wellbeing, we observe an increased vulnerability to poverty in cities. Figure 3 shows the annual growth rate of poverty and extreme poverty by area, which increased notably during the 2014 commodity price shock and the COVID-19 pandemic, revealing that urban poverty is more likely to grow during times of economic downturn, than rural poverty. This is likely because as households move out of poverty in cities, they often hover right above the poverty line, one employment loss or illness away from falling back into deprivation. Although rural poverty still fluctuates with economic shifts, it remains more stable and has decreased significantly since 2021.

Inflation is one of the factors behind these shifts. Rising living costs post-pandemic hit urban households hardest, pushing them into poverty and worsening conditions for those already poor. Urban households are also more tied to the market economy than rural ones, making them more vulnerable to fluctuations in the economy, which often translates into changes in employment. In contrast, rural livelihoods allow households to design informal coping strategies to shocks -such as subsistence farming, labor reallocating, seeking support from their community, or liquidating assets like livestock -that urban residents typically lack. Additionally, urban poverty often concentrates on informal settlements on the outskirts of cities, where overcrowding and limited access to basic services create further challenges.

This means that addressing poverty in urban and rural areas requires tailored strategies. Policies that work in rural areas, like boosting agricultural productivity and improving access to assets and markets, don’t fully address the needs of the urban poor, where rising housing costs and food inflation are significant concerns. But reducing poverty alone is not enough: public policy must also focus on fostering household resilience. By supporting families to build assets that can help them cope with future shocks, public policies can protect progress in human development and reduce the risk of backsliding into poverty.

Locations

Locations